There are some things we know intuitively to be true. And while the term “less is more” has grown more and more cliché, it still has that nugget of truth at its core.

Yet despite our supposed agreement, we don’t often ask why it rings so true. What’s so good about “less”?

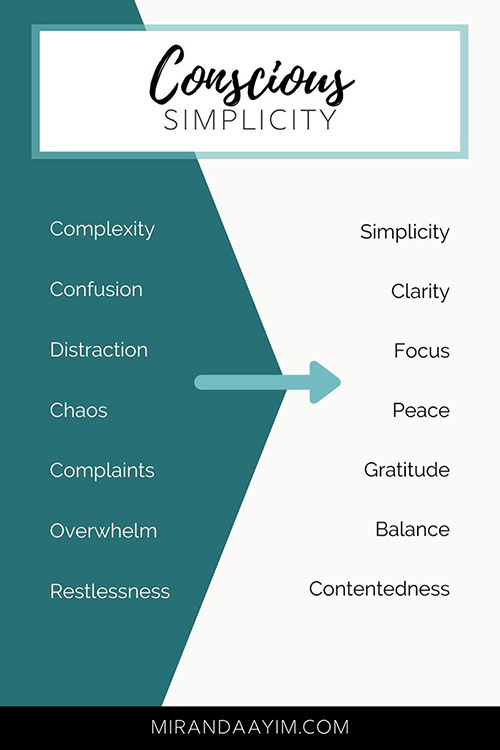

Well, “less” positively plays out in our life in many ways:

It reduces complexity and confusion

It refocuses your attention on the important

It reduces your need for more

It promotes gratitude and deep satisfaction

In order to reap these benefits, however, some evaluation is necessary. Conscious simplicity (and similarly, minimalism and essentialism) is a call to observe what’s in your life, what you’re adding to your life and what you want in your life. There’s a fundamental question at the core: why?

Why do I need this?

Why am I drawn to this?

Why must I do or say or be this?

Once we uncover the why, the what is a lot simpler. As in, what do I truly need in my life?

“The objective of the simple life is not to dogmatically live with less but to live with balance in order to realize a life of greater purpose, fulfillment, and satisfaction.”

– Duane Elgin

The Vital Few vs. The Trivial Many

Living simpler helps us avoid distractions and busyness that would take our attention away from what’s essential. And one of the first steps to determining what’s essential is to discern “the vital few from the trivial many.”1

An integral part of simplifying your life is determining “the vital few.”2

At first glance, it appears to be an easy task—you just need to think about what’s important to you. But what seems simple is quickly complicated by the focusing illusion, a phenomenon coined by psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman3

We drastically overestimate the importance of what’s in front of us. The simple act of focusing on something causes our mind falsely inflate its value.

I’ll use a personal example from when I was recently looking to buy a coffee grinder.

I like good coffee, but I’m not a connoisseur by any means. A good strong cup of coffee is ideal, but it’s the morning ritual that I find more valuable than anything.

However, an hour in to my Amazon search, I find myself seriously considering a professional grade grinder with approximately 125 functions that I will never use. But, I may need them some day and it does have a beautiful LED display, my mind argues.

Suddenly, having a high-tech, sleek gadget for my coffee-making became super important to me.

The focusing illusion takes our attention and turns it against us. If we’re not in touch with what we truly need, we’re quickly sucked into a purchase or decision that adds no value to our life other than sitting pretty on our counter with a hundred unused features.

I gave an example of a concrete item, but it goes beyond the physical into what we choose to spend our time, energy and attention on.

Maybe you’re thinking: Hey, if I have the money, time and space for more stuff, why not?

Well, there’s a few reasons why having more stuff (physical stuff, to-do stuff, or digital stuff) can be detrimental.

Option Overload

At face value, having options seems desirable. Why would you want less choice?

Well, apparently extensive choice just stresses us out.4 The more options we have, the more decisions we have to make and decision fatigue sets in pretty quickly.

Steve Jobs is the most popular example of using this to his advantage. A black turtleneck and jeans were his daily outfit. Removing irrelevant fashion choices left him with greater capacity to make important decisions throughout his day.

That’s why The Minimalists, capsule wardrobes and Marie Kondo are so popular. Less choice means less decisions means less stress.

By the way, more isn’t synonymous with better. If we apply Sturgeon’s Law, about 90% of everything is crap. Is it worth your time to sort through 100 options to find the one that’s 0.35% better than what you currently have?

Instead of “missing out” on all the options, we’re able to relish the freedom and lightness that comes with less—less decisions, less stuff, less noise. We’re left truly appreciating what’s in front of us.

“You cannot overestimate the unimportance of practically everything.”

John C. Maxwell

Distraction-mania

In an age of constant connection, we have a million things competing for our attention—from the number of channels on TV, to the list of things we need to complete, to the ads in our browser, to the social engagements in our calendar.

Just as our time is finite, so is our attention. We can only focus on one thing at a time and the lag time between switching tasks is exceedingly slow. In a UC Irvine study widely cited for showing that it takes us around 23 minutes to regain focus after our attention has shifted, I noticed an equally interesting finding:

“After only 20 minutes of interrupted performance people reported significantly higher stress, frustration, workload, effort, and pressure.”5

Can you imagine how many hours (and how much peace of mind) we’re losing each day simply because we have too many distractions around us?

The more low value things in our orbit, the more our attention is drawn from things that matter. Although perhaps harmless at face value, everything in the attention sphere is a trade off. If you pay attention to one thing, you can’t pay attention to something else.

Think of the list of emails waiting for you, or the flashing ads in your browser, or that new deluxe coffee grinder. They all seem pretty urgent and necessary, don’t they? (Thanks again, focusing illusion).

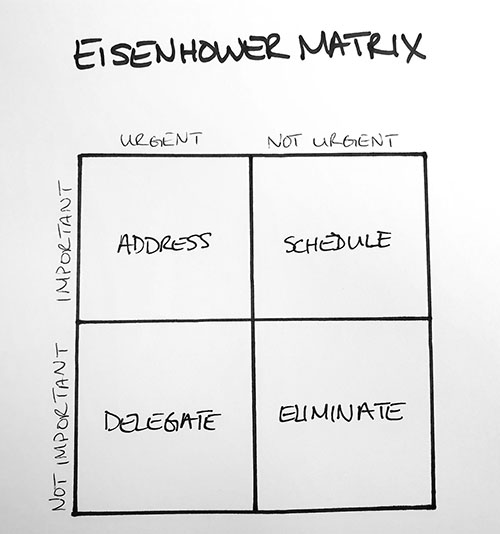

There’s a handy tool for determining what you should focus on and what you should ignore (read: aggressively eliminate). It’s The Eisenhower Matrix.

That upcoming family event that you need to find a photographer for? Make a note to circle back (Schedule). Your overgrown mess of a backyard? Hire your nieces and nephews (Delegate). Those unread newsletters and promotions for random stuff? Not worth it (Eliminate).

Even Napoleon, an important man with important tasks to attend to, apparently had his secretary hold all received correspondence for three weeks before opening. By that time, most of the “urgent” problems had been solved.

Conscious simplicity helps reassess what’s truly urgent and important. It pares down physical and mental distractions so that there is more room for the essential: the activities and goals that are worth our time, energy, and attention.

Personal Process

This doesn’t mean you need to exist on 15 pieces of clothing, live in an Airstream trailer or refuse to respond to email. It’s not about stripping yourself of anything and everything. It’s simply about being intentional about what you allow in your life.

It also don’t mean that you can’t buy a professional grade grinder. If you’ve determined that it’s a valuable addition to your life, have at it!

We have a tendency to compare, even in worthy pursuits like trying to simplify our lives. If your neighbour’s house looks like an advertisement for Spartan living, that doesn’t make her better than you. If your acquaintance has a penchant for high fashion, that doesn’t make you better than him.

Simplification is a personal process. What starts in the physical realm spills over into the mental and spiritual realm. It ends up being a tidying up overhaul—getting rid of the inessential distractions and hitting reset.

Footnotes

- McKeown, G. (2014). Essentialism: The disciplined pursuit of less. London: Virgin.

- McKeown, Greg. Essentialism: the Disciplined Pursuit of Less. London: Virgin, 2014.

- http://www.morgenkommichspaeterrein.de/ressources/download/125krueger.pdf

- Iyengar, Sheena S., and Mark R. Lepper. “When Choice Is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79, no. 6 (2000): 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.995.

- Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. In Computer-Human Interactions (CHI), Florence, Italy: ACM, 107-110. https://www.ics.uci.edu/~gmark/chi08-mark.pdf